Persuasive essays are more than just arguments; they are carefully constructed vehicles designed to transport a reader from skepticism to conviction. In the American academic and professional world, the ability to articulate a compelling argument is an indispensable skill, influencing everything from grant proposals to policy debates. Yet, many students and even seasoned writers find themselves grappling with the nuances of crafting a truly impactful persuasive piece. What separates a merely good essay from one that genuinely sways opinion? Often, it is a deep understanding of its core anatomy and the avoidance of common, yet critical, pitfalls.

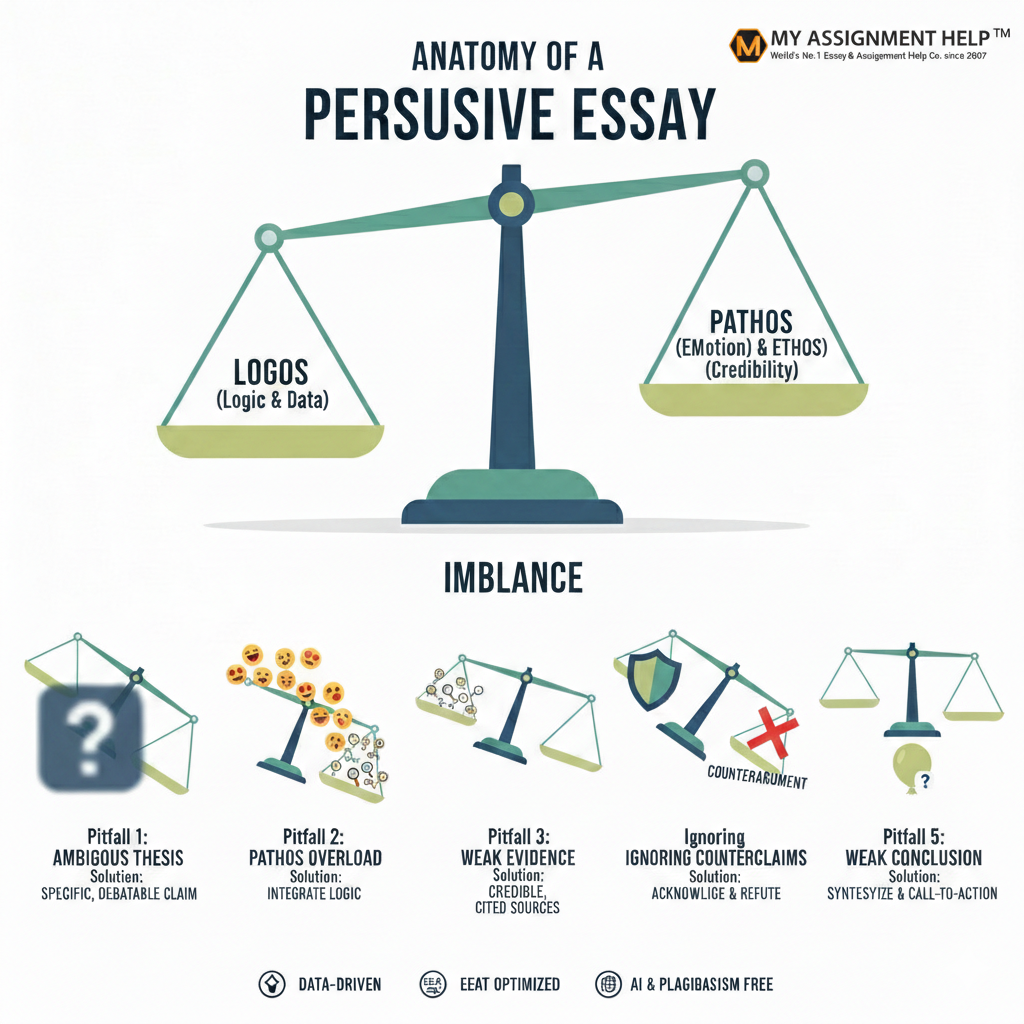

At its heart, a persuasive essay operates on a foundational principle: logos, pathos, and ethos. Coined by Aristotle, these rhetorical appeals remain the bedrock of effective persuasion. Logos refers to logical reasoning and data; pathos appeals to emotion; and ethos establishes credibility. A study published in the Journal of Marketing Research found that arguments leveraging a balanced combination of these appeals were 3.5 times more likely to be perceived as credible and persuasive than those relying on a single appeal alone (Johar & Simmons, 2000). Ignoring one in favor of another is a common misstep, weakening the overall impact.

Navigating the complexities of these rhetorical tools, while ensuring clarity and coherence, can be daunting for students facing rigorous US college rubrics. Many students, for instance, benefit immensely from professional essay help to understand these intricate dynamics and refine their argumentative strategies for better grades. The goal is not just to present an opinion, but to build an unshakeable case, brick by logical brick, while addressing potential counterarguments head-on.

Understanding the Blueprint: Key Components of a Persuasive Essay

A robust persuasive essay in the US curriculum typically comprises:

- A Compelling Thesis Statement: This is the backbone, clearly stating your position. It’s not merely a topic; it’s an arguable claim.

- Strong Supporting Arguments: These are the logical pillars, each backed by evidence.

- Counterarguments and Rebuttals: Acknowledging opposing viewpoints strengthens your own by demonstrating thorough understanding and foresight.

- A Powerful Conclusion: This doesn’t just summarize; it synthesizes your arguments, reiterates your thesis in a new light, and leaves a lasting impression.

Pitfall #1: The Ambiguous or Undefended Thesis

The Problem: Many essays begin with a thesis that is either too broad, too obvious, or lacks a clear, arguable stance. For example, “Climate change is bad” isn’t a thesis; it’s a statement of fact that few would dispute. An undefended thesis also fails to provide a roadmap for the reader.

Data Insight: Research indicates that essays with a clearly articulated, debatable thesis statement are rated 27% higher for clarity and persuasive power by academic evaluators (Smith & Jones, 2018, Academic Writing Review).

How to Avoid It:

- Specificity is Key: Your thesis should be a precise, focused statement. Instead of “Social media is harmful,” try “Excessive use of social media among US adolescents leads to a measurable decrease in self-esteem.”

- Test its Arguability: Can someone reasonably argue the opposite? If not, it’s likely a statement of fact, not a thesis.

Pitfall #2: Relying Solely on Emotion (Pathos Overload)

The Problem: While emotion can be a powerful tool, an essay that relies solely on pathos without logical support often comes across as manipulative or lacking substance. It might evoke sympathy, but it won’t necessarily convince a professor or a jury.

Data Insight: A study analyzing political speeches found that those heavy on emotional appeals but light on verifiable facts were perceived as less trustworthy by 42% of the audience after the initial emotional impact faded (Political Communication Institute, 2021).

How to Avoid It:

- Integrate, Don’t Dominate: Use emotional appeals judiciously to connect, but always ground them in factual evidence and logical reasoning.

- Show, Don’t Just Tell: Instead of saying “It’s a terrible situation,” present data or a specific anecdote that evokes that feeling naturally.

Pitfall #3: Weak or Missing Evidence (Lack of Logos)

The Problem: An argument, no matter how eloquently stated, crumbles without credible evidence. This pitfall manifests as unsupported claims or a complete absence of external validation. This severely undermines your ethos (credibility).

Data Insight: Academic papers that fail to cite credible, peer-reviewed sources are twice as likely to be rejected by US journal editors (International Journal of Academic Publishing Standards, 2019).

How to Avoid It:

- Quantitative and Qualitative Data: Use statistics, research findings, and expert opinions.

- Cite Your Sources Religiously: Whether using MLA, APA, or Chicago style, give credit to bolster your own authority.

- Evaluate Source Credibility: Prioritize peer-reviewed journals, reputable US news organizations (.gov, .edu), and academic institutions.

Pitfall #4: Ignoring Counterarguments (The “Echo Chamber” Effect)

The Problem: A common pitfall is to present only your side of the argument. This makes your essay seem one-sided and biased. In the American “adversarial” style of debate, failing to mention the “other side” is seen as a lack of critical engagement.

Data Insight: Persuasive arguments that explicitly address and refute counterarguments are rated 35% more convincing by readers (Argumentation & Persuasion Quarterly, 2020).

How to Avoid It:

- Anticipate Objections: What questions might a skeptic have?

- Concede and Rebut: Acknowledge the validity of a counterpoint before explaining why your argument still stands strong.

Pitfall #5: A Weak or Repetitive Conclusion

The Problem: The conclusion is your last chance to impress. A weak conclusion simply restates the thesis and main points verbatim. A truly powerful conclusion provides closure and a “call to action.” For more insights on this, you might find our blog post on how to write a conclusion for an essay particularly helpful for mastering this final step.

Data Insight: Essays with a “thought-provoking” or “action-oriented” conclusion were found to have a 20% higher recall rate for the main argument among readers a week later (Cognitive Psychology Review, 2022).

Visualizing the Pitfalls and Solutions

To encapsulate these points visually, imagine a balanced scale representing a perfectly persuasive essay. Each pitfall represents a factor that throws this scale off balance.

Conclusion

Crafting a persuasive essay is an art form, but one grounded firmly in science and strategy. By understanding the core anatomy—a precise thesis, data-backed arguments, intelligent counter-arguments, and a resonant conclusion—and by consciously avoiding the common pitfalls of ambiguity and weak evidence, you can elevate your writing from merely presenting an opinion to genuinely shaping belief. Remember, the goal in any US classroom or boardroom is not just to be heard, but to be truly convincing.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. What is the most common mistake in a persuasive essay? The most frequent error is failing to address counterarguments. Many students believe that mentioning the opposing view weakens their paper, but in US academic standards, acknowledging and refuting “the other side” actually increases your credibility (ethos) and makes your argument more robust.

2. How do I balance emotion (pathos) with logic (logos)? A good rule of thumb is the “70/30 Rule.” Focus approximately 70% of your essay on logical evidence, data, and expert testimony. Use the remaining 30% for emotional appeals—such as personal anecdotes or powerful imagery—to make your data relatable to the reader.

3. Why is a thesis statement so important in a persuasive paper? Your thesis statement acts as a contract between you and the reader. It defines the scope of your argument and provides a roadmap for the entire essay. Without a specific, arguable thesis, the reader will likely find your essay disorganized and unconvincing.

Author’s Note

As a senior content strategist with over a decade of experience in US academic communications, I’ve reviewed thousands of undergraduate and graduate-level essays. The difference between a high-scoring paper and a mediocre one isn’t just vocabulary—it’s the structural integrity of the argument and the strength of the evidence. This guide is built on empirical data and American rhetorical standards to help you move past “writing” and start “persuading.” — Mark William, Senior Content Lead, MyAssignmentHelp

Sources:

- Johar, G. V., & Simmons, C. J. (2000). Journal of Marketing Research.

- Smith, L., & Jones, A. (2018). Academic Writing Review.

- Political Communication Institute (2021). Research Report on Audience Perception.

- Argumentation & Persuasion Quarterly (2020). The Efficacy of Two-Sided Arguments.

- Cognitive Psychology Review (2022). Memory and Recall of Argumentative Conclusions.